As the Federal Reserve executes its policy shift from pandemic era generosity to inflation busting zeal, financial markets are at crossroads. It fears, not necessarily the exit of ‘easy’ money supply as much as a policy error, the kind that takes an economy with underlying consumer demand greater than pre-pandemic levels and leaves it without a pulse.

Global supply chain is not the only thing deserving of blame

So why the change of posture? As a group that prides itself on being data dependent, the policy shift makes sense. Very few of us set out to learn the proper pronunciations of the Greek alphabet through emerging Covid variant nomenclature. The spring of 2021 was supposed to be the proverbial spring of our post pandemic world, post supply-chain woes, post stimulus checks and certainly post 2,000 deaths per day.

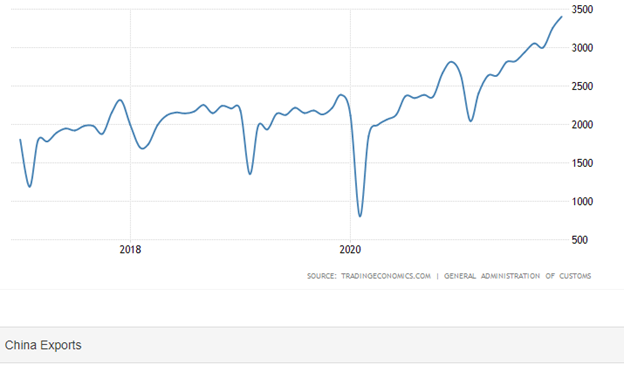

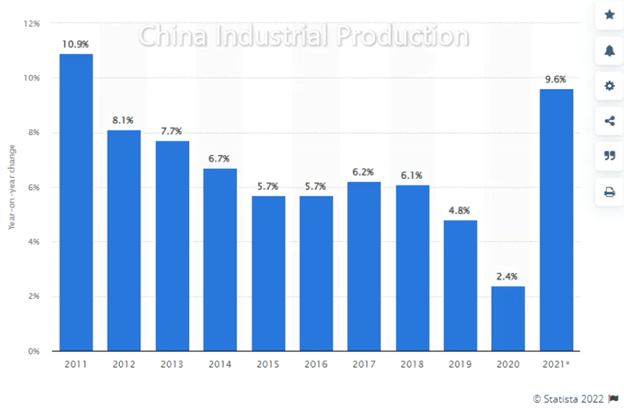

So far, the expectations of ‘stickiness’ of inflation have been wrong because longevity estimates of the pandemic have been wrong. As inflation extends into its second year, what gets lost in the headlines is the true health of global supply chains. A cursory look at the most covered elements of the supply shock such as semiconductors, ports and trucker shortages may suggest that supply chains are running below capacity. The truth is that global supply chains are pumping out more products than the recent pre-pandemic period. It is no match for the median American consumer that has a more robust balance sheet, comparatively low debt to income and wants to spend.

China’s production is 20% higher than at the start of 2020, achieved despite rolling lockdowns throughout the last two years. Copper, aluminum, and nickel production are all significantly higher than in 2019 yet global inventories are at multi-year lows. Years of under investment in mining, supplier redundancy, maritime shipping capacity are all to blame, without a short-term fix for any of these problems. The fix must come by way of moderating demand.

It is quite likely that the U.S. will see full employment in the next 12 to 15 months. With central bank’s one of two key mandates (full employment and inflation control) in sight, it is set to address the demand picture through higher rates. The key question here is whether a Fed, focused on price stability, can still be a friend to investors. Uncertainty around this very question is at the heart of market gyrations since mid-November. Recent history suggests yes, as recently as the fourth quarter of 2018.

Times like these test investors more than they test the companies they are invested in

As the stock market sold off early-stage growth stocks in December, money shifted into ‘blue-chip’ tech. Once the creme de la creme of tech names took a tumble, money flooded into rate-sensitive banks and household goods companies. After banks sell-off in mid-January, the handful of names remaining positive for the year are cell phone and insurance companies. The fact that the market is confused would be a massive understatement. Times like these test investors more than they test the companies they are invested in. Discomfort during these swings is normal, and they reveal what kind of investors we really are. Ask yourself if you cashed out in early 2020 or late 2018 or 2015, would that have improved your financial well-being?

As the effects of the last major stimulus from the American Rescue Plan begin to dissolve away, there is still an underappreciated scenario ahead where consumer demand starts to stair-step naturally to more normal levels, supply chains further increase capacity, and an improved supply-demand balance emerges without severe intervention. Until then, we remain committed to owning high-quality, innovation driving corners of the market where business models remain unaffected by the price correction.